Penguin Essentials, 2019, 365 p. First published 2007.

Addressing as it does the Armenian genocide of 1916 (though only in a historical sense,) this was the book that saw the author put on trial for “denigrating Turkishness,” but the charges were eventually dropped.

The novel’s main focus is on the Kazancı family, one with an unfortunate history of its male members dying at a young age. There is a hint of magical realism here, the more sweeping kind of narrative more or less alien to the Anglophone tradition, in any case a nod to the supernatural elements which often appear in fiction from other literary backgrounds. The Kazancıs have a cat named Sultan. (They’re now on Sultan the Fifth. This naming system though, did remind me of Mad Jack’s burro in The Life and Times of Grizzly Adams.)

The chapter titles all relate to foodstuffs – or at least substances which can be ingested; cinnamon, pine nuts, orange peels, etc, though one is water and the last potassium cyanide. For the Kazancıs are a family for which food occupies a central nurturing role. Many Turkish dishes are named or described during the course of the novel.

In the first chapter the then nineteen-year-old Zeliha Kazancı strides the streets of Istanbul wearing her trademark short skirt – which she will not relinquish even in later years. Under harassment she recites to herself “The Golden Rule of Prudence for an Istanbulite woman: When harassed on the street never respond” as that only fires up the enthusiasm of the harasser. (There are also Silver and Copper Rules of Prudence.)

Zeliha is on her way to a clinic to seek an abortion but, perhaps due to hallucinations brought on by anæsthetic or else a subliminal wish to carry the child – though the latter seems unlikely – becomes over-agitated and makes it impossible for the procedure to continue. The bastard of the title (though there is one other metaphorical candidate) could thus be Zeliha’s daughter, Asya, who is brought up among her aunts Banu, Feride and Cevriye, their mother, Grandmother Gülsüm, and the matriarch Petite-Ma. Acknowledging the unusual circumstances of Asya’s origins (in her late teens of the novel’s main timeline her father’s identity has still not been disclosed,) Zeliha is also known as aunty. The only son of the family, Mustafa, long ago left Istanbul for the US and has never returned. The aunts’ father had of course when still young succumbed to the curse on the family males. Even so, by the age of sixteen Asya had discovered that “other families weren’t like hers and some families could be normal,” a twist to that quote from Tolstoy. [https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/7142-all-happy-families-are-alike-each-unhappy-family-is-unhappy]

Asya is fixated on Johnny Cash and spends time in Café Kundera, associating with characters identified only by their attributes, the Non-Nationalist Scenarist of Ultranational Movies, the Closeted-Gay Communist, the Exceptionally Untalented Poet and the Dipsomaniac Cartoonist, who says the real civilization gap is not between East and West but between Turks and the Turks. “‘We are a bunch of cultured urbanites surrounded by hillbillies and bumpkins on all sides. They have conquered the whole city.’” The Exceptionally Untalented Poet says, “‘We are stuck between East and West …. the past and the future … the secular modernists … and the conventional traditionalists.’” In its own way this is a signal that the book could be read as a ‘condition of Turkey’ novel.* When one of them brings along a new girlfriend we are told of Asya that “When she met a new female she could do one of two things: either wait to see when she would start hating her or take the shortcut and hate her right away.”

Mustafa, in the US, has taken up with Rose, who was divorced from Barsam Tchakhmakhchian, a first generation Armenian American. Barsam and Rose’s daughter Armanoush (Amy,) is the second pivot of the plot, brought up as she was with her father’s family’s constant reinforcement of Armenian memories and attitudes vis-à-vis the Turks. Shafak has some fun depicting Amy’s date with a man she soon finds unsuitable, where they both contemplate plates of food whose arrangements are based on expressionist paintings. To resolve the conflict she feels between her US and Armenian heritages Amy decides to travel to Istanbul to visit her stepfather’s family, where her revelations about the treatment of her ancestors creates at first bewilderment.

“She, as an Armenian, embodied the spirits of her people generations and generations earlier, whereas the average Turk had no such continuity with his or her ancestors. The Armenians and the Turks lived in different time frames.” For Armenians “time was a cycle, the past incarnated in the present and the present birthed the future. For the Turks, time was a multihyphenated line, where the past ended at some definite point and the present started anew from scratch, and there was nothing but rupture in between.” Even Aunt Cerviye, as a history teacher, was unaware of the details or extent of the Armenians’ tribulations. For the aunts, the history of Turkey only began in 1923, with Atatürk’s reforms. (Such historical forgettings, or forgettings of history, are by no means confined to Turkey, though.)

In another expression of literary apartness, that rebuff to Western fiction’s conventional realism, Aunty Banu has – or claims to have – control of two invisible djinn, one on each shoulder; the good one, whom she calls Mrs Sweet, on the right, the bad one, Mr Bitter, on the left. It is from Mr Bitter she learns the truth about the Armenians’ sufferings. And about Asya’s father, news which she keeps to herself, though his identity is revealed later.

Shafak has her characters make more general observations too. Asya tells Amy, “When women survive an awful marriage or love affair … they generally avoid another relationship for quite some time. With men, however … the moment they finish a catastrophe they start looking for another one. Men are incapable of being alone.”

Curiously, Shafak at least twice used the word wee in the Scottish sense of small, as in “a wee bit.”

Some reviews I have seen online of The Bastard of Istanbul have been a bit sniffy, one even going so far as to say that on this evidence Shafak isn’t a good novelist. I suspect this means that reader had not had a wide experience of fiction from outwith the Anglosphere. Shafak’s writing has a brio, an exuberance, too often missing from that more staid inheritance.

Pedant’s corner:- *Turkey is now officially known as Türkiye; “wrack your nerves” (rack your nerves,) “and her cheeks sunk in” (sank in. There were other examples of ‘sunk’ for ‘sank’,) “as she laid still on a table” (as she lay still,) “phyllo pastry” (filo pastry,) “always on demand” (always in demand,) no introductory quotation mark when one chapter began with a piece of dialogue but there was with other chapters.

I bought this because Piercy normally writes SF (or what can be interpreted as SF) but this is a contemporary mainstream novel – for 1998 values of contemporary.

I bought this because Piercy normally writes SF (or what can be interpreted as SF) but this is a contemporary mainstream novel – for 1998 values of contemporary.

This is the first book of Barker’s trilogy about alumni of the Slade Art School in the run-up to the Great War. I read the second one,

This is the first book of Barker’s trilogy about alumni of the Slade Art School in the run-up to the Great War. I read the second one,  Here, we are in Moscow in 1913. Though educated in England, printer Frank Reid has spent most of his life in Russia, inheriting the business from his father, but that life is thrown into disarray when his wife Nellie ups and leaves leaving him with three children to cope with, Dolly, Ben and Annushka, and so he engages a young woman, Lisa Ivanovna, as a sort of nanny.

Here, we are in Moscow in 1913. Though educated in England, printer Frank Reid has spent most of his life in Russia, inheriting the business from his father, but that life is thrown into disarray when his wife Nellie ups and leaves leaving him with three children to cope with, Dolly, Ben and Annushka, and so he engages a young woman, Lisa Ivanovna, as a sort of nanny. This was Woolf’s last novel, published posthumously. A prefatory note by her husband said it was completed but not corrected nor revised, though he believes she would not have made any large alterations. I beg to differ.

This was Woolf’s last novel, published posthumously. A prefatory note by her husband said it was completed but not corrected nor revised, though he believes she would not have made any large alterations. I beg to differ. In this continuation of Charlotte Brontë’s story from Dark Quartet, she is in deep mourning for her late sisters and brother but left in effect to see to her father’s welfare on her own (except for the two servants.)

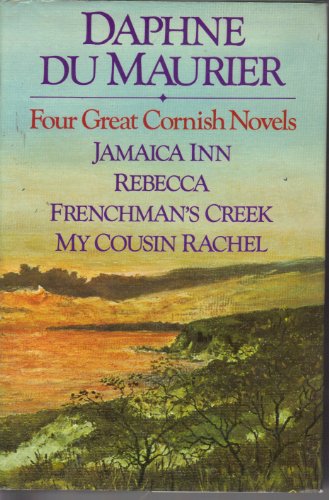

In this continuation of Charlotte Brontë’s story from Dark Quartet, she is in deep mourning for her late sisters and brother but left in effect to see to her father’s welfare on her own (except for the two servants.) How does the modern reader review an eighty-five year-old book with a large cultural imprint and a story perhaps familiar from TV or film adaptations? And one on which anyone reading the review may already have formed their own opinions? This is the problem with Rebecca, a book I have come to very late. Is there anything new to say about it?

How does the modern reader review an eighty-five year-old book with a large cultural imprint and a story perhaps familiar from TV or film adaptations? And one on which anyone reading the review may already have formed their own opinions? This is the problem with Rebecca, a book I have come to very late. Is there anything new to say about it? In the novel’s first paragraph Lucrezia de’ Medici – married to Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, for less than a year – realises that her husband intends to kill her. Forthcoming chapters relating her time at the retreat called Fortezza, near Bondeno, to which Alfonso has taken her, presumably for this sinister purpose, are in the same present tense as this one is. These are interspersed with past tense chapters unfolding the tale of her life up to that point as the third daughter of

In the novel’s first paragraph Lucrezia de’ Medici – married to Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, for less than a year – realises that her husband intends to kill her. Forthcoming chapters relating her time at the retreat called Fortezza, near Bondeno, to which Alfonso has taken her, presumably for this sinister purpose, are in the same present tense as this one is. These are interspersed with past tense chapters unfolding the tale of her life up to that point as the third daughter of