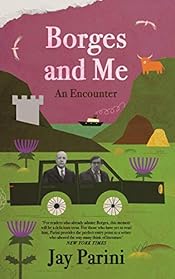

Borges and Me: an encounter by Jay Parini

Posted in Reading Reviewed at 12:00 on 14 December 2024

Canongate, 2021, 309 p.

In his youth, as a post-graduate student at St Andrews escaping being drafted to Vietnam and contemplating a thesis on George MacKay Brown (a prospect his tutor deprecated on the grounds that Brown was still alive,) the author, a nervous individual from Scranton, Pennsylvania, with an overbearing mother also to escape, met Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, who was on a visit to the town to meet a local academic, Alastair Reid, with whom Parini had formed a friendship. Despite Borges’s fame, Parini had never read a word of his.

In his youth, as a post-graduate student at St Andrews escaping being drafted to Vietnam and contemplating a thesis on George MacKay Brown (a prospect his tutor deprecated on the grounds that Brown was still alive,) the author, a nervous individual from Scranton, Pennsylvania, with an overbearing mother also to escape, met Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, who was on a visit to the town to meet a local academic, Alastair Reid, with whom Parini had formed a friendship. Despite Borges’s fame, Parini had never read a word of his.

The book is constructed, and reads, like a novel, starting with a recounting of the author’s learning of Borges’s death one morning fifteen years, plus a wife and three sons, later, triggering memories of the impact Borges had made on him. Borges and Me goes on to relate the circumstances of that meeting, the car journey through the Highlands with Parini acting as the blind Borges’s eyes it led to, and how it changed him. Thirty-six years on from that, Parini was encouraged to write it all up as a complete narrative. Such a tardy account cannot be in all respects absolutely accurate, some elisions and compressions must occur. Parini’s afterword uses the phrase ‘novelistic memoir’ to characterise it. As a result the book is therefore probably more effective than a pure memoir.

In many ways the title is apposite. Borges and Me is really more about Parini than Borges. His mother on learning of his proposed transatlantic destination said, “‘Are you crazy? Nobody goes to Scotland!’” but relented, saying, in recognition of his avoiding the Army, “‘At least you’ll be safe in Scotland, though Scotch girls have a bad reputation,’” (really?) “‘and the men apparently wear skirts.’”

We hear of Parini’s preoccupations of the time; the unread letters from the draft board he stuffed in a drawer, his learning to use the word ‘rucksack’ for ‘backpack’ and what he describes as the pretentious ‘garden’ for ‘yard’, his struggles connecting with women.

The descriptions of St Andrews are of course very familiar to me. But Alastair Reid’s warning to Parini, contrasted with his experiences in the Pacific War (World War 2 was still a huge presence in so many lives in the 1960s and 70s,) “‘Remember, this isn’t a university, it’s a film set. Don’t be fooled. The lecturers, even the students, are actors. They’re here to attract tourists,’” is only partly true. St Andrews has the golf as well to do that.

An anecdote Reid told him prompted the thought, “Was this the essence of storytelling? Did one simply have to relate a tale in a believable fashion, with the authority of the imagination?” Which is of course a comment on the present enterprise – and of fiction writing in general.

And there are reflections on the Scotland of that age. Reid says, ‘What I don’t like about Scotland is that virtue is taken for achievement. And narrowly defined. We’re always judged in this fucking country…. They don’t even take off their clothes to fuck here.’ This last prompted Reid to suggest special Scottish pyjamas, with flaps in the appropriate place so that the deed could be done as secretively as possible.

(Aside. Actually I read once that the Inuit peoples of the Arctic have clothes that are indeed equipped in such a way; but that would be for purely practical purposes, to avoid the cold, not as a moral imperative.)

As portrayed here Borges was a formidable personality with an intimidating breadth of knowledge – among other things he corrected Parini’s pronunciation of Scone (Palace.) “‘It rhymes with spoon. It’s a Pictish word’” – and also aware of his own mortality. The failings of the body did at one point lead to a comic episode in a B&B in Killiecrankie. The only toilet was off the bedroom of the widowed lady proprietor and Borges had consumed a few pints.

Parini does not pity Borges his blindness as it in some ways freed him. “No wonder he lived so fully in the great room of his mind.”

At one point Borges apparently stated, “‘Israel as a state inspires me. An intractable situation, very sad, unsolvable with Palestine: competing and equally valid claims.’” Intractable indeed.

He also had an old man’s wistfulness for the loves of his youth (and present) Doña Leonor and Maria Kodama, a contrast with the young Parini’s stated lack of experience

The final stop on the car journey, for a pilgrimage across Drumossie Moor, the battlefield of Culloden, has poignant resonances, though I must say the tourist facilities there have changed a lot since that time. Parini describes them as basic indeed. When I revisited a few years ago the visitor centre was as bright and commercial as you would find anywhere.

But Borges’s influence was profound. “One felt somehow more intelligent, more learned and witty, in his presence. The universe itself felt more pliable and yielding, and so available.”

Borges and Me is a delightful book. An elegant tribute to the great man, a tribute to the uncertainties of youth and the potentially beneficial upshots of unexpected encounters.

Pedant’s corner:- mostly written in USian. “Orkney, a remote island off the north coast of Scotland” (Orkney is an archipelago, not a single island,) bandanna (x 2, bandana,) “a tony girls’ school in Kent” (??? Tiny? Tory?) “in pigeon Spanish” (pidgin Spanish that would be,) “following the M 90 through the town of Kinross” (the M 90 bypasses Kinross, you have to make a small detour to go through the town,) crenulations (as a castle feature it’s spelt crenellations,) “a lunch of mulligatawny and cheese rolls” (I hope it was mulligatawny soup and cheese rolls; a filling of mulligatawny and cheese does not sound appetising,) “he invariably shined warmth on his characters” (shone warmth,) “chomping at the bit” (it’s champing.) Robbie Makgill (more likely McGill,) “‘We played hooky’” (supposedly said by a Scot. It’s not a phrase we use for truanting, ‘dogging it’, ‘bunking off’, or ‘plunking’, as it was called in my youth.)