Dead Catch by T F Muir

Posted in Reading Reviewed, Scottish Fiction at 12:00 on 28 September 2025

Robinson, 2019, 377 p.

Following on from Life For a Life I would most likely never have looked at this, crime fiction not really being my thing, except that the good lady had borrowed it from the local library so I thought I might as well.

A fishing boat washed up on Tentsmuir beach is found to contain a body restrained by wire in such a way that any movement would have resulted in a slow death. The boat belonged to Joe Christie who had disappeared – along with the boat – several years ago. The victim isn’t Christie though but Stooky Dee, an alleged associate of big Jock Shepherd, Scotland’s criminal kingpin. Muir makes much use of italicising alleged in the book in relation to Shepherd’s activities. DCI Andy Gilchrist, based in St Andrews, investigates the case.

Gilchrist has problems with his adult children and difficulties with the forensic pathologist Dr Rebecca Cooper whose brief liaison she cut off when she decided to reconcile with her husband. These attempts to humanise our hero are something of a distraction from the main plot. There is a nice moment, though, when Gilchrist tells his daughter when she says he knows how to talk to women as if he knows what they’re thinking, “No man knows what any woman is thinking.”

It soon turns out others of Shepherd’s henchmen, Cutter Boyd and Hatchet McBirn, have been killed recently but it seems the police in Strathclyde, Shepherd’s main area of operations, do not want Gilchrist muscling in on the case.

Further complications arise from Gilchrist’s DS Jessie Janes’s brother Tommy – on the run accused of murder, though Jessie doesn’t think he did it – contacting her about information he wants to give her.

All is mixed up with a big drug deal the Strathclyde force – along with HM Government – is hoping will lead to the arrests of major dealers, for which they send DI Fox, a supercilious creature to retrieve the case files from Fife.

Things become a bit too conspiracy laden when Gilchrist and (Jessie) Janes are tied up in a lock-up garage in Anstruther before a shoot-out resolves their problem.

This book confirmed that modern crime fiction is not for me. I doubt I’ll sample Muir’s work again. (It’s also enough to give anyone an aversion to visiting Fife.)

Pedant’s corner:- “to go back onboard” (back on board,) “a dumpster” (not a UK term. Muir’s sojourn in the US has got to him. We say ‘skip’, or [maybe] ‘wheelie-bin’,) “as if everyone …. were indoors” (as if everyone … was indoors,) “driven to the scrappies and dumped” (not a plural; a possessive: ‘to the scrappy’s’.) “Capisci?” (it’s spelled ‘Capisce’,) “right from the get-go” (‘right from the start’; please,) “when the caller finally gave out” (gave up,) “that all was not well” (that not all was well.)

The author is of course the doyenne of

The author is of course the doyenne of  The author has previously displayed his middle Eastern background in a couple of books,

The author has previously displayed his middle Eastern background in a couple of books,  I noticed early on while reading this book how different the style was compared to the same author’s

I noticed early on while reading this book how different the style was compared to the same author’s  This is the second of McDermid’s Karen Pirie books. I read the first

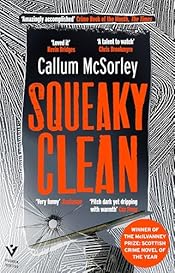

This is the second of McDermid’s Karen Pirie books. I read the first  “The reception area had been designed with an eye to vomit and violence.” Thus begins this book, which if you hadn’t already known this was a crime novel would certainly have alerted you instantly.

“The reception area had been designed with an eye to vomit and violence.” Thus begins this book, which if you hadn’t already known this was a crime novel would certainly have alerted you instantly. Richard Papen was brought up in Plano in California, a place he regards as a backwater. Nevertheless, he has made it to an elite college at Hampden in Vermont. His parents were not well off and he feels the contrast between himself and other students there. At first he tries not to be found out, but such things are hard to disguise. After originally being turned down as student of Greek by its professor Julian, Richard comes into the orbit of his rather small and close-knit class cohort, Francis, Henry, Edmond (known as Bunny,) and twins Charles and Camilla. (Those last two names perhaps now have more of a frisson than they would have had when Tartt wrote the book.) Richard overhears the five arguing about a Greek translation and provides them with a neat solution which encourages them to petition Julian to accept him.

Richard Papen was brought up in Plano in California, a place he regards as a backwater. Nevertheless, he has made it to an elite college at Hampden in Vermont. His parents were not well off and he feels the contrast between himself and other students there. At first he tries not to be found out, but such things are hard to disguise. After originally being turned down as student of Greek by its professor Julian, Richard comes into the orbit of his rather small and close-knit class cohort, Francis, Henry, Edmond (known as Bunny,) and twins Charles and Camilla. (Those last two names perhaps now have more of a frisson than they would have had when Tartt wrote the book.) Richard overhears the five arguing about a Greek translation and provides them with a neat solution which encourages them to petition Julian to accept him. Alison McCoist has been all but shunned in Glasgow’s police after she made a mistake in believing the confession of a man called Knightley to the murder of a young pregnant woman. The real culprit remains at large and DI McCoist – who has enough on her plate already what with her name being similar to a well-known former footballer (‘I’ve heard all the jokes already’) and only seeing her twin children under access conditions at weekends – is as a result widely thought to be on the take.

Alison McCoist has been all but shunned in Glasgow’s police after she made a mistake in believing the confession of a man called Knightley to the murder of a young pregnant woman. The real culprit remains at large and DI McCoist – who has enough on her plate already what with her name being similar to a well-known former footballer (‘I’ve heard all the jokes already’) and only seeing her twin children under access conditions at weekends – is as a result widely thought to be on the take.