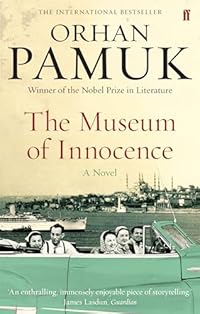

The Museum of Innocence by Orhan Pamuk

Posted in Museums, Other fiction, Reading Reviewed, Orhan Pamuk at 12:00 on 26 September 2012

Faber and Faber, 2009, 734 p. Translated from the Turkish, Masumiyet Müzesi, by Maureen Freely.

This is the tale of our narrator, Kemal Basmacı, a relatively well to do son of a Turkish business man, though he would say it was that of the love of his life, his distant not-quite relative, the shopgirl Füsun Keskin. As the novel starts Kemal is enjoying his carefree lifestyle, helping to run his father’s business, plus having sex with his intended, Sibel. A few weeks before their engagement party he meets Füsun again (they had been childhood acquaintances) and the pair take to making love in the afternoons. Being Turkey in the 1970s – though actually extra-marital relations were not entirely comment free then even in the West; certainly not in Scotland – the potential for ruin of her reputation is extreme. When Kemal falls in love with Füsun the outlines of a tragedy are in place.

Like a lot of novels set in repressive settings (not only for example in Egypt (The Yacoubian Building) but also Soviet era Czechoslovakia (The Unbearable Lightness of Being) the importance of sex infuses the story. More importantly here, it is the question of a woman’s virginity, or lack of it, on marriage that creates Kemal’s dilemma, Füsun’s family’s response to that problem a formidable obstacle to a happy resolution. The Museum of Innocence is trading on the perennial great themes of literature through the ages; love, sex and death. At one point the narrator opines that a love story with a happy ending is pretty well not worth telling. His mother (too late) tells him that in a country where men and women can’t be together socially, can’t even have a conversation, there is no such thing as love. If any woman shows interest the man is conditioned to pounce on her like a starving animal.

The Museum of Innocence of the novel’s title is Kemal’s shrine to Füsun’s memory. The narrative is like the museum’s catalogue, a description of the various stages of their relationship, exhibits of all the items Kemal has collected which connected her to him. In some places it as if the museum’s curator is speaking to us. A bit of meta-fictional post-modern gamesmanship occurs when an entry ticket to the museum is printed on one of the pages and also when the novelist Orhan Pamuk intrudes into his own novel as a very minor character. This is finessed in the final chapter by a not wholly convincing device which nevertheless confers a degree of perspective on Kemal’s story.

The evocation of Turkish life is interesting, its teetering on the brink of what Kemal’s crowd saw as modernity, its conflict with tradition. The vicissitudes of Turkish politics of the time, the civil strife, the military coups, the saturation with Atatürk’s image and memory, are mentioned but more or less in passing; indeed are there to point up that life went on notwithstanding them. Pamuk’s implicit critique of Turkish mores isn’t overstated, though. A salient feature was the tendency of the characters to smoke cigarettes. The fug of burnt tobacco almost leaps off the page: the book could come with a health warning. Is it the same still in Turkey, I wonder?

Kemal’s narration is measured, even, and his actions presented as reasonable but they are certainly obsessed and smack of a kind of madness. This is not unknown to Pamuk, of course. In the last chapter Kemal is referred to as “not quite right in the head.” Obsessive love is a kind of madness, I suppose. The novel and the Museum are presented as Kemal’s attempts to reclaim the sense of his own life from others’ interpretation of it. He may be deluded, but like Hamlet said, there is method in it.

The translation is into USian, but that was fine; Kemal had spent some time in the US in his youth. (There was only one sentence which struck me as awkward. In 700 odd pages that’s not bad going.)

In such a long story it is hard to avoid longueurs. That Pamuk broadly manages this despite more or less nothing happening to progress Kemal’s situation for many years is testament to his ability. I’ll be reading more of Pamuk.

Tags: Orhan Pamuk, Other fiction, Museums

Silent House by Orhan Pamuk – A Son of the Rock -- Jack Deighton

13 December 2012 at 12:00

[…] in The Museum of Innocence the tensions between Turkey and âthe West,â tradition and modernism, religion and the secular, […]

The Gaze by Elif Shafak – A Son of the Rock -- Jack Deighton

12 August 2023 at 12:01

[…] of Gazes. This, especially the tenor of the extracts from it, reminded me a bit of Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence. B-C says its entries are secretly linked to each other “‘a shaman’s cloak of forty patches […]