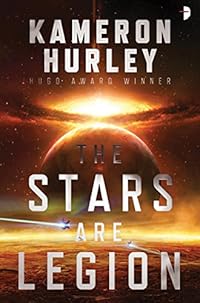

Angry Robot 2017, 397 p Reviewed for Interzone 270, May-Jun 2017.

Lit by an artificial sun, the worlds of the Legion hang in space. Massive orbs, they are living things covered externally by tentacles that simultaneously reach out but also offer protection to their world’s inhabitants. Their interiors are sticky and moist, biology taking the functions of such things as floors, walls and lifts. The worlds, though, are dying, with patches of rot blotching their surfaces. Beyond the misty veil that shrouds the sun lies the Mokshi, the only world to have moved out from the usual orbits of the Legion. As a result the Mokshi is an object of envy and conquest; but it is defended fiercely. Anat, Lord of Katazyrna, has a metal arm whose power is lost and she wishes to conquer the Mokshi in order to restore it and (literally) make a new world.

Each chapter here is prefaced by an aphorism by-lined, “Lord Mokshi, Annals of the Legion”. The narrative viewpoint, though, is shared between Zan and Jayd, once lovers, neither of whom are particularly sympathetic characters. At least twice as many chapters are devoted to Zan, who has lost her memory but is the only one of Katazyrna’s army ever to penetrate the Mokshi and survive. She is told she has made the attempt and returned many times.

The first set piece is a fairly standard piece of military SF as Katazyrna’s latest army attacks the Mokshi. However, the prospect this holds out of endless space battles is misleading. Hurley’s attention is more on the somewhat complicated relationship and backstory between Zan and Jayd.

It doesn’t take very long to work out that there are only women on these worlds. Hurley does not make anything of this – except in her afterword – it is merely a factor of this scenario, the society she has decided to portray. The mechanics of how their inhabitants become pregnant are obscure, though; even the mothers seem in the dark. Also, the birth products may be non-human, “Each world produces what it needs.” But in a strange mix of this magical-seeming biology with hi-tech, womb transfer can be effected surgically. Indeed we find Zan has donated hers and its contents to Jayd.

Neither does Lord Mokshi’s identity remain a mystery to the attentive reader, becoming obvious long before Hurley confirms it.

Interference from the forces of Bhavaja makes the attack fail and Anat decides on an alliance with these erstwhile enemies. To this end she arranges a marriage between Jayd and Rasida, Lord of Bhavaja. Jayd’s pregnancy is an important aspect of the deal. Bhavaja has not had a birth for some while. For a long time, to help Zan penetrate the Mokshi, Jayd has been working secretly towards this end.

The wedding is accompanied by a human sacrifice. This is only one of the many gory incidents in the book exemplified by Rasida’s despairing philosophy expressed later, “There’s no such thing as love in the Legion. There is birth and there is death. That’s all.” By this time Rasida has not kept her word, destroying Ana in the process, while Zan was thrown into Katazyrna’s recycler.

Which is where things begin to get bogged down. As well as what are in effect no more than monsters devouring the material to be recycled (Hurley seems to relish the details but they are oddly uninventive) Zan finds a woman living in the belly of the world, Das Muni, who helps her to escape to the next level.

The main body of the book is taken up with Zan’s journey up through the strata of the living world where the obstacles she meets are overcome perhaps a little too easily and she picks up another two handy companions.

One of Gene Wolfe’s prescriptions for writing fiction is that if your hero(ine) goes on a journey you must describe it. Well, there’s describing and then there’s overdoing it. The journey here is certainly important to the outcome as it provides Zan with clues to both her past (she has done all this before, remember) and future but it reminded me of the seemingly endless trek across the Ringworld in one of Larry Niven’s series of novels; it’s there more to show us the author’s invented world rather than advance the plot. Together with the emphasis on violence here that, for me, reduced engagement. It may be more to others’ taste.

The following did not appear in the published review.

Pedant’s corner:- “I change directions” (direction,) auroras (aurorae.) “The security crosses their arms and puts their backs to me” (its arms, its backs,) “a bevy …. begin” (begins,) “the whole of Katzyrna pour out” (the whole pours out,) in the hopes (in the hope,) maw in sense of mouth (sigh; it’s a stomach,) “a hunger than no meal can satisfy” (that no meal,) “fearful that the council will change their mind” (its mind,) the moths become less and less (fewer and fewer,) a missing start quote when a chapter began with a piece of dialogue, “I motion to Das Muni to lower the litter …… I motion to Das Muni to lower our own load” without the load being picked back up in the meantime, “I … try to see the where it’s fallen from” (no “the” needed,) “lined in row upon row” (by row upon row,) “if it is was my child” (if it was,) “that something had happened to her leg” (the narration is always present tense; so, something has happened to her leg,) “One is full of clear liquid. The other is full of purple liquid.” (clear here is contrasted with a colour; since clear does not mean colourless, the purple liquid could equally have been clear,) “Zan gets up now and wipe her hands” (wipes.)