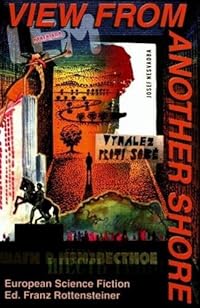

View From Another Shore – European Science Fiction. Edited by Franz Rottensteiner

Posted in Reading Reviewed, Science Fiction at 12:00 on 5 December 2012

European Science Fiction Liverpool University Press, 1999, 256p

This is a 1999 reprint of a collection first published in 1973. Rottensteiner’s introduction for this volume bemoans the fate of SF in Eastern Europe since the Berlin Wall came down and the fact that non-Anglophone SF (even Australian SF) does not get much of a foothold in the world markets. It then goes on to discuss non-British European SF with respect to its main standard bearers, Stanisław Lem and the Strugatsky Brothers, heaping praise on the latter (comparing them to Philip K Dick) but tasking Lem for poor characterisation, misanthropy and misogyny. Yet the book fails to include a Strugatsky story and opens with one by Lem!

It is now almost 15 years since that introduction and Rottensteiner’s complaint still holds good. Very little SF written in other languages appears in English translation. For a genre which claims to operate over the whole of space and time that is a shocking indictment. But the fact remains that SF is primarily a US form and the US on the whole isn’t outward looking. Plus the costs involved may not return a publisher’s investment; certainly in Britain.

The content of View From Another Shore embodies a wide sweep of the continent. (I note, here though, that none of the contributors is female.) Rottensteiner argues that unique Europeanness cannot be attributed to these works of SF, no common characteristics that set them apart; arguing for only one literature since each writer is an individual. I don’t entirely agree with this view as it is possible to discern over a body of a national literature – even within SF – certain recurring themes and preoccupations (though some writers will of course transcend this.)

If there is such a thread in this book it is that the stories tend to didacticism, in general shy away from human interaction, are more interested in the situation than the people affected by it. Perhaps this distancing is an artefact of translation though.

A short comment on each story is below.

In Hot Pursuit of Happiness by Stanisław Lem. Translated from the Polish, Kobyscze, by Michael Kandel.

Yes, there is a dry quality to Lem’s writing. His fiction is more in the nature of thought experiment or philosophical tract than stories in the true sense. To expect rounded characters is to miss the point rather. A similar complaint can be made of Olaf Stapledon, after all. Yet has he been criticised for poor characterisation et al? Without the thread of empathy/sympathy it does make the reading harder, though.

The Valley of Echoes by Gérard Klein. Translated from the French, La Valleé des échos, by Frank Zero.

Explorers on Mars look for evidence of past alien life.

Observation of Quadragnes by J -P Andrevon Translated from the French, Observation des Quadragnes, by Frank Zero.

The Quadranges in question are humans, snatched from Earth by an “Extractor” to be studied by aliens. Cue much ado about sexual behaviour.

The Good Ring by Svend Åge Madsen. Translated from the Danish, Den gode ring, by Carl Mamberg.

A farmer picks up a ring which pulls him into a different reality where advanced creatures show him what his life would have been like on parallel Earths.

Slum by Herbert W Franke. Translated from the German, Un den Slums, by Chris Herriman.

Humans have taken to sub-ocean habitats. An expedition to the surface finds remnants of humanity scraping a living there.

The Land of Osiris by Wolfgang Jeschke. Translated from the German, Osiris Land, by Sally Schiller

Everything north of sub-Saharan Africa has been devastated by nuclear and biological war. In the Muslim dominated liveable regions of the continent mutants or the light-skinned are persecuted and killed. A foreigner (Master Jack) from southern Africa takes our main narrator, Beschir ibn Hassan el Sadun, as a companion to investigate strange occurrences in the dangerous reaches of the Nile. This setting is fascinating and well-handled but the story takes another tack as their journey unfolds and connections to ancient Egypt are made.

Captain Nemo’s Last Adventure by Josef Nesvadba. Translated from the Czech, Posledni dobroduství kapitána Nemo, by Iris Urwin.

A spaceman called Nemo (because his craft is named the Nautilus) is sent on a time-dilation journey to investigate what seems to be a systematic extinguishing of stars. In style this is very reminiscent of R A Lafferty’s Space Chantey.

The Altar of the Random Gods by Adrian Rogoz. Translated from the Romanian, Altarul zeilor stohastici, by Matthew J O’Connell.

The survivor of a once-in-the-lifetime-of-the-universe sequence of accidents limps into the presence of three cybernetic “gods.”

Good Night, Sophie by Lino Aldani. Translated from the Italian, Buonanotte Sofia, by L K Conrad.

A star of Oneirofilms – immersive dream experiences that are better than reality – tries in real life to interact with the customers for her performances.

The Proving Ground by Sever Gandosky. Translated from the Russian, Poligon, by Matthew J O’Connell.

This story features an ultimate weapon, a mind-reading tank, and shoots at an easy target, military commanders.

Sisyphus, the Son of Aeolus by Vsevolod Ivanov. Translated from the Russian, Sisif, syn eola, by Adele L Milch.

A warrior from Ancient Greece is on his way home when he encounters Sisyphus. This story is myth or fable rather than SF.

A Modest Genius by Vadim Shefner. Translated from the Russian, Skromnyi genii, by Matthew J O’Connell.

A prolific inventor diffident about promoting his inventions stumbles through life.