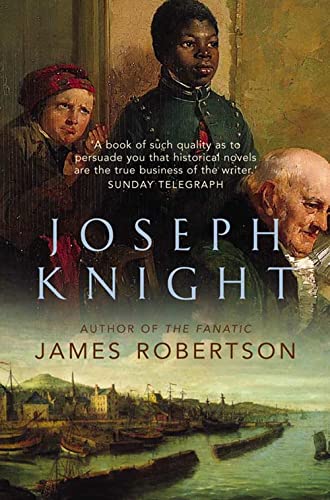

Joseph Knight by James Robertson

Posted in Reading Reviewed, Scottish Fiction, James Robertson at 14:00 on 20 September 2010

Fourth Estate, 2004. 372p

Based on a legal case brought in the eighteenth century, celebrated at the time but soon forgotten, this novel pushes a fair number of Scottish buttons, with settings from Drumossie Moor, 1746, (Culloden) to the Perthshire of 1802, taking in Dundee, Edinburgh and the Scottish Enlightenment – complete with cameo appearances from Boswell and Johnson – before ending up in Wemyss, Fife, in 1803. It also ranges all the way to the Jamaican sugar plantations and back.

Though we don’t hear from or see him (except for two words of dialogue or in the pages of a notebook) until nearly halfway through, and then only incidentally till the last section, the character of Joseph Knight hangs over the book – almost like a ghost.

The tale is carried to fruition by Archibald Jamieson, who is engaged by Sir John Wedderburn, sometime Jacobite rebel and refugee from Culloden, later sugar planter and bogus doctor in Jamaica, long returned to Scotland a wealthy man and now owner of Ballindean Estate, to ascertain the whereabouts, or remaining earthly existence, of Joseph Knight, once Sir John’s personal possession (brought to Scotland as a marker of success) but who petitioned the Scottish courts in the 1770s to attain his freedom. Jamieson learns of the Jamaican episodes via a journal given to him by Sir John’s daughter but written by her long deceased uncle during his sojourn on the island. Despite at first finding no trace of him and assuming him dead, Jamieson nevertheless becomes fascinated by Knight.

The book is structured in four sections, two much shorter book-ending the longer middle pair: Wedderburn, where Sir John ruminates over his life from the windows of Ballindean with its fine views over the policies down to the River Tay; Darkness, mostly concerned with the life Wedderburn and his brothers led in Jamaica; Enlightenment, wherein the court case on which the book depends is led up to and described; and Knight, a somewhat melancholic coda.

The narrative is multi-stranded with various viewpoint characters in each section, all of whom are portrayed in their roundnesses. If anyone needs a demonstration of how to carry this off Joseph Knight is the perfect example.

There is a peculiarity. Robertson has his characters use the word “neger” to describe black slaves (and freemen.) Perhaps that is indeed how the n-word was pronounced in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries but it still seemed a trifle odd, as if he was somehow afraid to outrage modern day readers.

Dealing as it does with those novelistic biggies life and death, plus freedom, servitude and the peculiar institution of slavery – but not so much with sex – it’s not surprising that Joseph Knight garnered such praise; not to mention the Saltire Scottish Book of the Year Award. It does, however, lose focus a little in the two long sections. In particular the scenes involving Boswell were not entirely necessary.

The characterisation is superb, however; all the people portrayed, even minor characters, seem idiosyncratic living, breathing beings and Robertson’s ability to inhabit the minds of his centuries-gone agonists sympathetically is striking. The only exception to this is Knight himself, who remains a shadowy figure.

But even this is appropriate. It is his absence from the main lives depicted here, the void he left, that they circle around.

This is a fine book: perhaps not so good as Robertson’s first, The Fanatic, but certainly surpassing his later the testament of Gideon Mack.

Tags: Other fiction, Scottish Fiction, slavery, Joseph Robertson

The Professor of Truth by James Robertson – A Son of the Rock -- Jack Deighton

14 October 2014 at 23:15

[…] in Covenanting times, the testament of Gideon Mack has a modern day Kirk Minister meet the devil, Joseph Knight examines the (in danger of being forgotten) colonial and slave-owning legacy, while And the Land […]