Throughout the 1950s, the early 1960s, through the late 60s efflorescence of the New Wave and into the 1970s and 80s a stream of English authors came to prominence in the SF field and had novels published in Britain. To my mind there was a clear distinction in the type of books all these authors were producing compared to those emanating from across the Atlantic and that certain characteristics distinguished the work emanating from either of these publication areas. While Bob Shaw was a notable Northern Irish proponent of the form during this period and Christopher Evans flew the flag for Wales from 1980 something kept nagging at me as I felt the compulsion to begin writing. Where, in all of this, were the Scottish writers of SF? And would Scottish authors produce a different kind of SF again?

Until Iain M Banks’s Consider Phlebas, 1987, contemporary Science Fiction by a Scottish author was so scarce as to be invisible. It sometimes seemed that none was being published. As far as Scottish contribution to the field went in this period only Chris Boyce, who was joint winner of a Sunday Times SF competition and released a couple of SF novels on the back of that achievement, Angus McAllister, who produced the misunderstood The Krugg Syndrome and the excellent but not SF The Canongate Strangler plus the much underrated Graham Dunstan Martin offered any profile at all but none of them could be described as prominent. And their works tended to be overlooked by the wider SF world.

There was, certainly, the success of Alasdair Gray’s Lanark in 1981 but that novel was more firmly in the Scottish tradition of fantasy and/or the supernatural rather than SF (cf David Lindsay’s A Voyage To Arcturus, 1920) and was in any case so much of a tour de force that it hardly seemed possible to emulate it; or even touch its foothills.

David Pringle noted the dearth of Scottish SF writers in his introduction to the anthology Nova Scotia where he argued that the seeming absence of Scottish SF authors was effectively an illusion. They were being published, only not in the UK. They (or their parents) had all emigrated to America. Though he has since partly resiled on that argument, it does of course invite the question. Why did this not happen to English SF writers?

It was in this relatively unpromising scenario that I conceived the utterly bizarre notion of writing not just Science Fiction but Scottish Science Fiction and in particular started to construct an SF novel that could only have been written by a Scot. Other novels may have been set in Scotland or displayed Scottish sensibilities but as far as I know I’m the only person who deliberately set out to write a novel of Scottish SF.

It could of course simply be that there was so little SF from Scotland being published because hardly anyone Scottish was writing SF or submitting it to publishers. But there were undoubtedly aspirants; to which this lack of role models might have been an off-putting factor. I myself was dubious about submitting to English publishers as they might not be wholly in tune with SF written from a Scottish perspective. I also thought Scottish publishers, apparently absorbed with urban grittiness, would look on it askance. I may have been completely wrong in these assumptions but I think them understandable given the circumstances. There is still no Scottish publisher of speculative fiction.

With Iain M Banks and Consider Phlebas the game changed. Suddenly there was a high profile Scottish SF writer; suddenly the barrier was not so daunting. And Phlebas was Space Opera, the sort of thing I was used to reading in American SF, albeit Banks had a take on it far removed from right wing puffery of the sort most Americans produced. Phlebas was also distant from most English SF – a significant proportion of which was seemingly fixated with either J G Ballard or Michael Moorcock or else communing with nature, and in general seemed reluctant to cleave the paper light years. Moreover, Banks sold SF books by the bucketload.

There was, though, the caveat that he had been published in the mainstream first and was something of a succès de scandale. (Or hype – they can both work.)

[There is, by the way, an argument to be had that all of Banks’s fiction could be classified as genre: whether the genre be SF, thriller, in the Scottish sentimental tradition, or even all three at once. It is also arguable that Banks made Space Opera viable once more for any British SF writer. Stephen Baxter’s, Peter Hamilton’s and Alastair Reynolds’s novel debuts post-date 1987.]

As luck would have it the inestimable David Garnett soon began to make encouraging noises about the short stories I was sending him, hoping to get into, at first Zenith, and then New Worlds.

I finally fully clicked with him when I sent The Face Of The Waters, whose manuscript he red-penned everywhere. By doing that, though, he nevertheless turned me into a writer overnight and the much longer rewrite was immeasurably improved. (He didn’t need to sound quite so surprised that I’d made a good job of it, though.)

That one was straightforward SF which could have been written by anyone. Next, though, he accepted This Is The Road (even if he asked me to change its title rather than use the one I had chosen) which was thematically Scottish. I also managed to sneak Closing Time into the pages of the David Pringle edited Interzone – after the most grudging acceptance letter I’ve ever had. That one was set in Glasgow though the location was not germane to the plot. The idea was to alternate Scottish SF stories with ones not so specific but that soon petered out.

The novel I had embarked on was of course A Son Of The Rock and it was David Garnett who put me in touch with Orbit. On the basis of the first half of it they showed interest.

Six months on, at the first Glasgow Worldcon,* 1995, Ken MacLeod’s Star Fraction appeared. Another Scottish SF writer. More Space Opera with a non right wing slant. A month or so later I finally finished A Son Of The Rock, sent it off and crossed my fingers. It was published eighteen months afterwards.

I think I succeeded in my aim. The Northern Irish author Ian McDonald (whose first novel Desolation Road appeared in 1988) in any case blurbed it as “a rara avis, a truly Scottish SF novel” and there is a sense in which A Son Of The Rock was actually a State Of Scotland novel disguised as SF.

Unfortunately the editor who accepted it (a man who, while English, bears the impeccably Scottish sounding name of Colin Murray) moved on and his successor wasn’t so sympathetic to my next effort – even if Who Changes Not isn’t Scottish SF in the same uncompromising way. It is only Scottish obliquely.

So; is there now a distinctive beast that can be described as Scottish Science Fiction? With the recent emergence of a wheen of Scottish writers in the speculative field there may at last be a critical mass which allows a judgement.

Banks’s Culture novels can be seen as set in a socialist utopia. Ken MacLeod has explicitly explored left wing perspectives in his SF and, moreover, used Scotland as a setting. Hal Duncan has encompassed – even transcended – all the genres of the fantastic in the two volumes of The Book Of All Hours, Alan Campbell constructed a dark fantastical nightmare of a world in The Deepgate Codex books. Gary Gibson says he writes fiction pure and simple and admits of no national characteristics to his work – but it is Space Opera – while Mike Cobley is no Scot Nat (even if The Seeds Of Earth does have “Scots in Spa-a-a-ce.”)

My answer?

Probably not, even though putative practitioners are more numerous now – especially if we include fantasy. For these are separate writers doing their separate things. I’ll leave it to others to decide whether they have over-arching themes or are in any way comparable.

PS. Curiously, on the Fantastic Fiction website, Stephen Baxter, Peter Hamilton and Alastair Reynolds are flagged as British – as are Bob Shaw, Ian McDonald, Christopher Evans and Mike Cobley – while all the other Scottish authors I’ve mentioned are labelled “Scotland.” I don’t know what this information is trying to tell us.

*For anyone who hasn’t met the term, Science Fiction Conventions are known colloquially as Cons. There are loads of these every year, most pretty small and some quite specialised. The Worldcon is the most important, an annual SF convention with attendees from all over the globe. It’s usually held in the US but has been in Britain thrice (Glasgow 2, Brighton 1) and once in Japan, to my knowledge. The big annual British SF convention is known as Eastercon because it takes place over the Easter weekend.

Edited to add (6/6/2014):- Margaret Elphinstone should be added to the list above of Scottish authors of SF. Her first SF book The Incomer appeared from the Women’s Press in 1987, the same year as Consider Phlebas, but I missed out on it then. My review is here.

See also my Scottish SF update.

Edited again to add (4/4/18) Elphinstone’s sequel to The Incomer is A Sparrow’s Flight which I reviewed here.

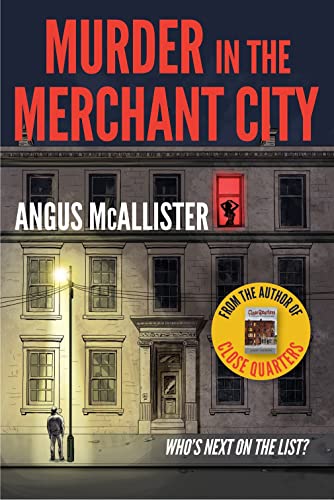

The book’s title perhaps says it all – there are murders, some scenes are set in Glasgow’s Merchant City – but is a trifle misleading. The action centres not on the Merchant City itself but on the so-called Merchant City Health Centre, a massage parlour – and an establishment with all the connotations that description of a business inevitably invokes. This is staffed by women in white coats – at least until they take them off to get down to offering extras. The most important of these to the plot are the beautiful Miranda, with the beaming smile and that way of saying, “How are you?” to her regulars, no nonsense up-front Claudia, the conventionally attractive Candy, the more homely in style Annette, and new girl Justine.

The book’s title perhaps says it all – there are murders, some scenes are set in Glasgow’s Merchant City – but is a trifle misleading. The action centres not on the Merchant City itself but on the so-called Merchant City Health Centre, a massage parlour – and an establishment with all the connotations that description of a business inevitably invokes. This is staffed by women in white coats – at least until they take them off to get down to offering extras. The most important of these to the plot are the beautiful Miranda, with the beaming smile and that way of saying, “How are you?” to her regulars, no nonsense up-front Claudia, the conventionally attractive Candy, the more homely in style Annette, and new girl Justine.